Welcome to True Crime Tuesday where we review, recommend and generally obsess over everything crime-related.

Last week, Netflix released part two of Making a Murderer, a docu-series focusing on the murder of Teresa Halbach. Even though Steven Avery and his nephew Brendan Dassey were convicted for Halbach’s murder in 2007, the fight for justice is far from over. That’s because both Dassey and Avery have maintained their innocence since the day they were arrested.

The post-conviction litigation process for murder cases in the U.S. is long, complicated, and frankly, a long shot. The odds are against them at every step and their case is further complicated by the taped confession of Brendan Dassey. It’s hard for police, the prosecution, juries, and the general public to understand why anyone would ever confess to something they didn’t do—especially something as serious as murder. But according to The Innocence Project, of the more than 350 wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence since 1989, 28% of them involved false confessions.

To learn more about why an innocent person would confess, check out True Stories of False Confessions by Rob Warden and How the Police Generate False Confessions: An Inside Look at the Interrogation Room by James L. Trainum. Netflix also has a show called The Confession Tapes that shows the true stories of innocent people who confessed to a crime—and how the justice system took advantage of them.

In the meantime, here are five cases that relied heavily on a false confession to get a conviction.

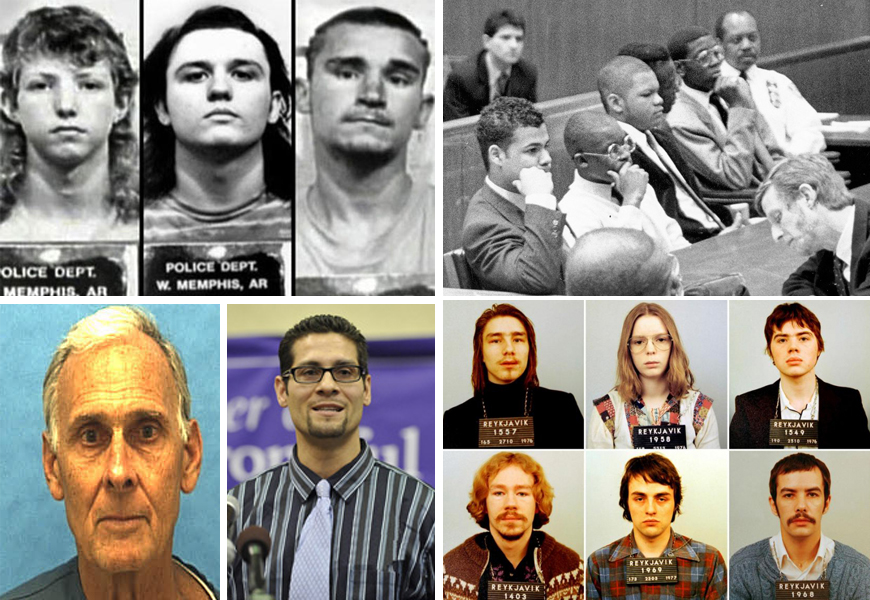

West Memphis Three

Arguably one of the most infamous cases of wrongful conviction in U.S. history, the West Memphis Three, Jessie Miskelley, Jason Baldwin, and Damien Echols spent 18 years behind bars in large part because of a coerced false confession from Miskelley. The West Memphis police were investigating the triple homicide of three 8-year-old boys when information from a local woman named Vicki Hutcheson and her son Aaron led them to Miskelley and, by association, Echols and Baldwin.

There is a long list of unethical practices associated with the West Memphis Three investigation but Miskelley’s confession is one of the worst parts. Along with his IQ being well below average, Miskelley also demonstrated multiple times that he didn’t know any of the crucial details of the case. His story changed over and over and much of it didn’t fit with the facts the police already knew. Still, Miskelley’s coerced confession led to the arrest of both Baldwin and Echols even though there was no physical evidence linking them to the crime. Miskelley later recanted and refused to testify against Baldwin and Echols. All three of them were still convicted and it took DNA testing, three HBO documentaries, a lot of publicity and hard work, and eventually Alford pleas before the three men were finally released from prison.

Central Park 5

The Central Park jogger case was one of the most widely publicized crimes of the 1980s. On April 19, 1989, 28-year-old Trisha Meili was raped and assaulted while jogging in Central Park, leaving her in a coma for 12 days. Five juvenile males—four African American and one Hispanic—were arrested on the same night and charged with the attack on Meili and various other attacks that happened the same night. One of the accused, Yusef Salaam later claimed that while he was at the station, he heard the police beating up one of the other boys in the next room before saying to him “You realize you’re next.” Although the suspects (except Salaam) confessed on tape in the presence of a guardian, they all recanted within weeks saying they had been intimidated, lied to, and coerced into making false confessions.

Even though the physical evidence found via a rape kit pointed to a sixth, unknown suspect, all five boys were convicted and sentenced to anywhere from 5 to 15 years in prison. It wasn’t until 2001 that convicted serial rapist and murderer Matias Reyes admitted to committing the assault on Meili. The physical evidence proved his claim to be true although he was not prosecuted because the statute of limitations was up and he was already serving a life sentence for his other crimes. Although they’d already completed their sentences, the convictions against all five boys were vacated in 2002.

John Purvis

In November 1983, Susan Hamwi was found stabbed and strangled to death in her home. Her 18-month-old daughter Shane was also found dead in her crib due to neglect. 41-year-old John Purvis was known as the “town weirdo” because of his unusual behaviour caused by chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia and frequent panic attacks. Police interrogated Purvis, allegedly yelling at him and intimidating him, all of which his mother heard from the next room. She refused to let police speak with her son again, but they found a way to get to him when she wasn’t around. They put so much pressure on him that he finally confessed to murdering Hamwi—which the police took as fact even though there was absolutely no physical evidence linking him to the crime scene.

Although a judge ruled the original taped confession inadmissible in court, Purvis had also confessed to his psychiatrist, and that confession was allowed into evidence. The jury convicted Purvis based on his second confession and he was sentenced to life in prison. Years went by before detectives looking into old cases decided to investigate a claim that a man named Robert Beckett Sr. had murdered a girl fitting Susan Hamwi’s description. Eventually the truth came out: Susan’s estranged—and abusive—husband Paul had paid two men including Beckett $14,000 to kill his wife. Purvis was released after serving nine years in prison.

Juan Rivera

Juan Rivera was 20 years old when he was questioned by police in connection to the rape and murder of 11-year-old Holly Staker. After being questioned for several days, Rivera, who had a history of mental illness, confessed to the murder in a statement that was inconsistent with the known facts of the case. He was interviewed again and the detectives asked many leading questions, feeding him the right information along the way. Rivera was tried and convicted based on his confession even though there was no physical evidence linking him to the crime and he was wearing an ankle monitor from a previous conviction that indicated he hadn’t left his home on the night of the murder.

Rivera’s conviction was then overturned in 1993 and he was retried in 1998. An eye witness (who was only 2 years old at the time of the crime) testified and identified Rivera as the murderer, and he was convicted again. In 2004, DNA evidence led to his convicted being vacated, but in 2009 he was tried and found guilty a third time. Finally, in 2011, his conviction was overturned for the last time and the appellate court barred prosecutors from retrying Rivera for the murder charge ever again. Rivera later received a $20 million settlement, the largest ever wrongful conviction settlement in US history.

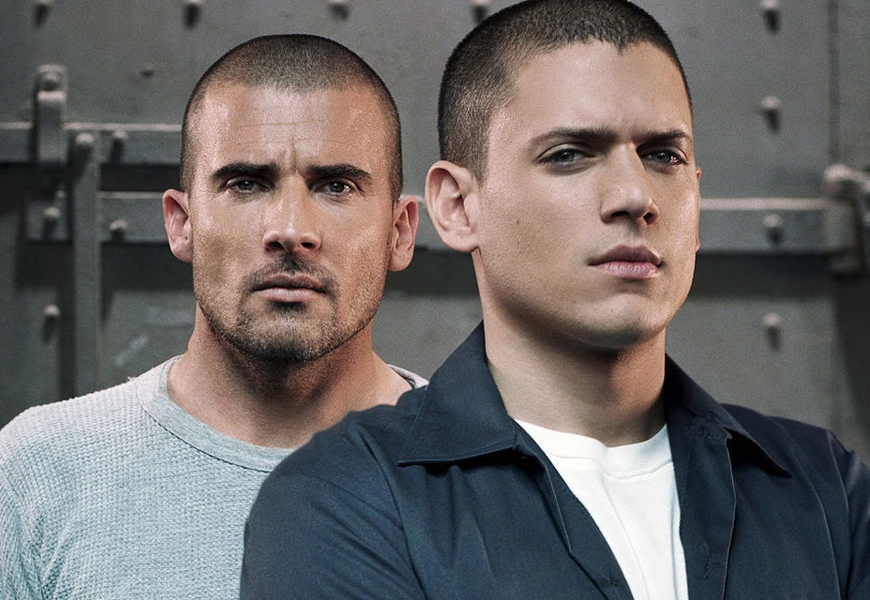

The Guðmundur and Geirfinnur case

The most infamous murder case Iceland has ever seen might not have been murder at all. In 1974, two men, Guðmundur Einarsson and Geirfinnur Einarsson (no relation) disappeared without a trace about approximately 10 months apart. Although there was no evidence to suggest foul play, the police were convinced the cases were linked and must have been murder. Two years later, 20-year-old Erla Bolladottir was questioned on an unrelated fraud charge when she indicated she might know something about the disappearances. She implicated her boyfriend Saevar Ciesielski and four of his friends who were all brought to the station for questioning.

What followed was an extreme case of coercion involving weeks of solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, and even water torture which led to all six of them confessing to either participating in or covering up the murders of the two men. It took years before the case received more attention and it was determined that the six accused suffered from

Memory Distrust Syndrome which is defined as “a profound distrust of your own memory, particularly during lengthy interrogation, where you begin to accept you’ve been involved in a crime which you have nothing to do with.” In September 2018, after the Supreme Court of Iceland reheard the case, all the men were acquitted or murder. If you want more details on the case (and there are a lot more details), check out the documentary Out of Thin Air.