European traditions tied to a third-century monk, combined with pieces of folklore, a 1823 poem by Clement Clarke Moore and a political cartoonist, all helped create the jolly old man in a red suit…

By Christopher Turner

Santa Claus – also known as Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Kris Kringle, Father Christmas or simply Santa – has a long history steeped in Christmas traditions. Today, he is generally depicted as a jolly old man with a white beard, often with glasses, who’s wearing a vibrant red suit trimmed with white fur, along with a black leather belt and boots, and who carries a bag full of gifts for good girls and boys on Christmas Eve. He also has a deep hearty laugh, frequently rendered in Christmas literature as “ho, ho, ho!” But why does he look like that and where did he come from?

The modern figure of Santa Claus is based on numerous folklore traditions from around the world, the most significant dating all the way back to the third century, when Saint Nicholas became the patron saint of children. Here’s the story of the original Santa Claus…and how that figure evolved into a jolly old man in red who, with the aid of Christmas elves, makes toys in his North Pole workshop to bring to children around the world during the late evening and overnight hours on Christmas Eve.

The legend of Saint Nicholas: the original Santa Claus

The legend of Santa Claus can be traced back hundreds of years to a monk named Saint Nicholas (270–343 AD). Saint Nicholas of Myra, also known as Nicholas of Bari, was an early Christian bishop of Greek descent who was born on March 15, 270, in the time of the Roman Empire, in Patara, near the maritime city of Myra in the southwest of modern-day Turkey.

Little is known about the historical Saint Nicholas; however, he has become the subject of many legends because of the stories told of his piety and kindness. A devout Christian, he lost both of his parents as a young man and it is said that he gave away all of his inherited wealth and travelled the countryside helping the poor and sick throughout his lifetime.

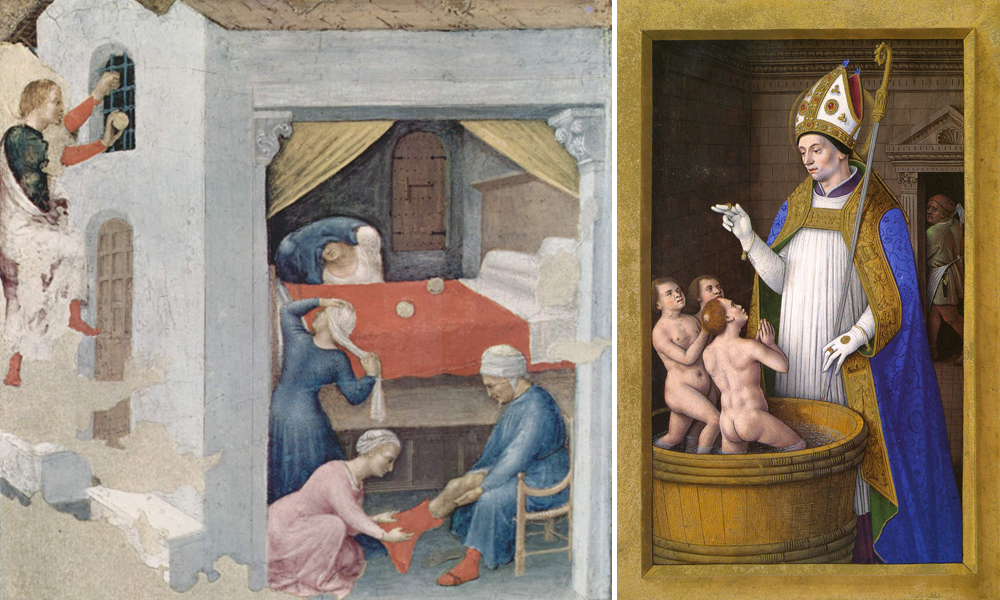

One of the best-known stories tells how Saint Nicholas saved three young women from being forced into prostitution; he dropped bags of gold through the windows of their house so that their father could afford a dowry that would enable them to marry. Another story tells of a terrible famine, where a butcher captured and killed three young children, planning to sell them off as meat. Saint Nicholas found the children being pickled in a barrel, and brought them back to life.

Over the course of many years, Saint Nicholas’s popularity spread; he became known as the protector of children and sailors, and was associated with gift giving.

Saint Nicholas died in Myra on December 6, 343, and the anniversary of his death became his feast day (every Christian saint has a feast day or commemorative festival, intended to recognize and celebrate that saint). During the Middle Ages, often on the evening before Saint Nicolas Day, children were given gifts in his honour.

By the Renaissance, Saint Nicholas was the most popular saint in Europe – so popular, in fact, that December 6 was traditionally considered to be a lucky day to make large purchases or get married. His popularity remained until the 1500s and the time of the Reformation, a religious movement that led to the development of Protestantism, which turned away from the practice of honouring saints. As Protestantism rose, German theologian and religious reformer Martin Luther (1483–1546) moved the celebrations and gift giving associated with Saint Nicholas from December 6 to December 25, because he disapproved of the Catholic veneration of saints and thought the traditional date of Christ’s birth a more appropriate date.

From Holland to New York

While the veneration of saints was discouraged throughout most of Europe, the Dutch continued to celebrate the feast day of Saint Nicholas on December 6, and it wasn’t long before his image had been secularized and he was imagined to deliver presents.

At the time it was a common practice for children to put out their shoes the night before the feast of Saint Nicolas, and in the morning, they would discover the gifts that Sint Nikolaas (Dutch for Saint Nicholas) had left for them. Sint Nikolaas was also referred to by his Dutch nickname, Sinterklaas or Sinter Klaas.

That tradition migrated to North America with the first Dutch immigrants, who settled along the Hudson River on Manhattan Island in 1624. The first records of these Dutch immigrants bringing the legend of Sint Nikolaas (and Sinterklaas) to America can be traced to the end of the 18th century. In December 1773, and again in 1774, a New York newspaper reported that groups of Dutch families had gathered to honour the anniversary of Sint Nikolaas’s death.

In 1804, John Pintard, a member of the New York Historical Society, distributed woodcuts of Saint Nicholas at the society’s annual meeting. The background of the engraving contains now-familiar Santa images, including stockings filled with toys and fruit hung over a fireplace. Then, in 1809, Washington Irving helped to popularize the Sinter Klaas stories when he referred to Saint Nicholas as the patron saint of New York in his book The History of New York.

The English origins of Father Christmas

As stories of Sinterklaas began gaining ground in Holland and eventually across Europe, the separate legend of Father Christmas emerged in England, where they no longer kept the feast day of Saint Nicholas. Father Christmas was a symbol of the Christmas season and Christmas Day in England, dating back as far as the 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII. The physical appearance of Father Christmas varied, but he was often depicted not as a gentle giver of gifts but as a large, merry old man in green or scarlet robes lined with fur who presided over festive parties. And that’s largely because Christmas was celebrated differently in England, with much more emphasis on entertainment for adults.

“He was essentially concerned with the adult world, personifying feasting and games; he had no connection with presents, and he was not treated with much respect, being generally a burlesque figure of fun,” wrote Ronald Hutton in Stations of the Sun (1996).

However, by the first half of the 19th century, Christmas was changing in England. With the Victorian focus on family life and children, it would no longer be just a time for drinking, feasting and making merry. And this new kind of Christmas needed a new kind of old man to represent it.

Christkind, Jultomten, Père Noël and La Befana

Of course, Saint Nicholas and Father Christmas are not the only figures connected to Christmastime – there are similar figures and Christmas traditions around the world. For example, Christkind or Kris Kringle was believed to deliver presents to well-behaved Swiss and German children. Meaning “Christ child,” Christkind is an angel-like figure often accompanied by Saint Nicholas on his holiday missions. In Scandinavia, a jolly elf named Jultomten was thought to deliver gifts in a sleigh drawn by goats. Père Noël is responsible for filling the shoes of French children with gifts, and in Italy, there is a story of a woman called La Befana, a kindly witch who rides a broomstick down the chimneys of Italian homes to deliver toys into the stockings of lucky children.

Eventually, the many different pagan and Christian traditions of Europe were consolidated in America into a single figure.

A cartoonist forges a new identity for St. Nick

Gift giving, mainly centred around children, has been an important part of the Christmas celebration since the holiday’s rejuvenation in the early 19th century. Prior to the early 1800s, Christmas was a religious holiday, plain and simple. However, in the early 1800s, several forces began to slowly transform it into the commercial fête we know and celebrate today: mainly, the wealth generated by the Industrial Revolution created a middle class that could afford to buy presents, and factories meant mass-produced goods.

As a result, Saint Nicholas went through many transformations. Stores in North America began to advertise Christmas shopping in 1820, and by the 1840s, newspapers were creating separate sections for holiday advertisements, which often featured images of the newly popular ‘Santa Claus.’

Examples of the Christmas holiday also began to appear in popular literature during this time, from Episcopal minister Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (more commonly known by its first verse, “’Twas the Night Before Christmas”) to Charles Dickens’ book A Christmas Carol, which was published in 1843.

Moore’s poem helped popularize the now-familiar image of a Santa Claus who flew from house to house on Christmas Eve in “a miniature sleigh” led by eight flying reindeer to leave presents for deserving children. “A Visit from St. Nicholas” created a new and immediately popular American icon.

Other writers and artists added new layers to the legend, and gradually ‘Santa Claus’ took over from Saint Nicholas. For several decades of the 19th century, he took a variety of forms – tall and short, fat and thin, his robes a rainbow of colours.

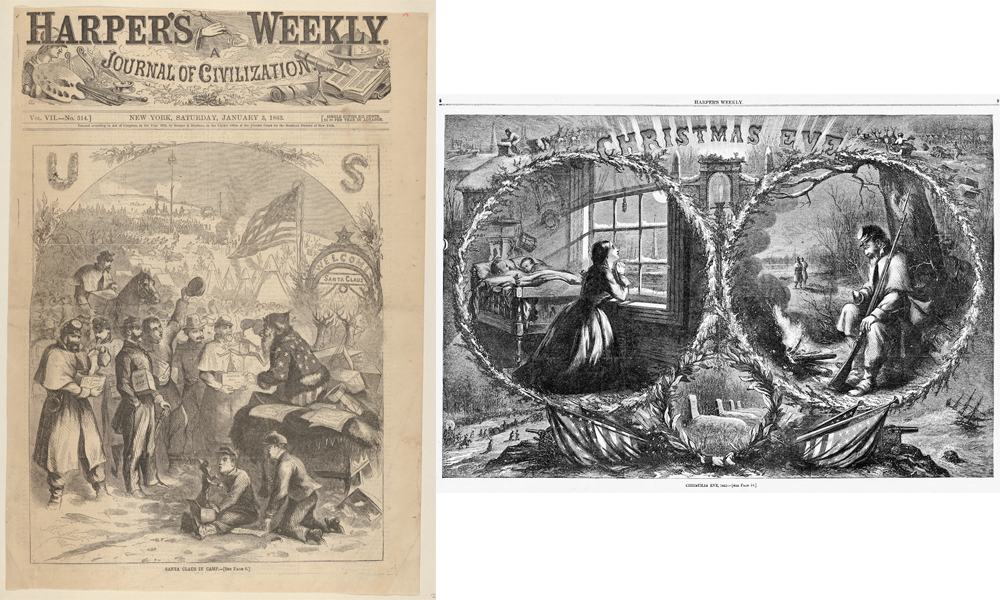

On January 3, 1863, the illustrated magazine Harper’s Weekly published two images by German-born American political cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840–1902) that would cement the direction of modern-day Christmas and Santa Claus. Nast found his inspiration from the 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” as well as the folklore tales of Saint Nicholas and Father Christmas. The first illustration shows Santa dressed in the stars and stripes of the American flag, distributing presents to Union troops in an army camp during the American Civil War. A second illustration in the issues features Santa in his sleigh, then going down a chimney. That’s shown in the periphery of the drawing; at the centre, in separate circles, are a woman praying on her knees and a soldier leaning against a tree.

“In these two drawings, Christmas became a Union holiday and Santa a Union local deity,” writes Adam Gopnik in a 1997 issue of the New Yorker. “It gave Christmas to the North – gave to the Union cause an aura of domestic sentiment, and even sentimentality.”

And so, beginning with the January 1863 drawings, Nast began to immortalize the mythic figure of Santa Claus. Though they varied from year to year, Nast’s Santa drawings appeared in Harper’s Weekly until 1886, amounting to 33 illustrations in total. His illustrations for “A Visit from St. Nicholas” were hugely popular, and he introduced the world to Santa’s workshop as well as the notion that Santa’s base of operations could be found at the North Pole. Nast eventually did more than any other artist to set the standard for Santa’s classic look. By 1881, Nast had perfected his vision of Santa, as seen in his “Merry Old Santa Claus” for Harper’s Weekly.

This version of Santa Claus had the red of Saint Nicholas’s bishop’s robes, the big belly of jolly Father Christmas, and the beard of so many pagan figures – a true cultural palimpsest.

Coca-Cola didn’t invent Santa

How many times have you heard somebody say that Coca-Cola designed the modern Santa Claus as part of an advertising campaign? Stop telling people that.… It’s a myth.

Nast’s first illustrations of a “modern” Santa Claus came out in 1863, and by 1881 he had perfected the version. In fact, artists had been portraying Santa almost exclusively in red since 1870. Coca-Cola didn’t start using Santa Claus in its advertising until 1933. Even if you were to confine your search to Santa in American soft drink advertisements, you would find, for example, a thoroughly modern Santa Claus in advertisements for White Rock Beverages mineral water that came out in 1915 and again in 1923–1925.

The Coca-Cola Company did, however, help to further define the images of Santa Claus in pop culture with their incredibly popular advertisements, which started in 1931 with illustrator Haddon Sundblum.

Commercial Christmas and Santa

By the 1830s, and certainly no later than the 1850s, the legend of Santa Claus, by that name, was undeniably part of mainstream culture in North America and throughout the rest of the world. And as Santa Claus in his fur-lined red suit gained popularity, retailers with commercial interests found it to their advantage to endorse Santa Claus and Christmas gift giving. The rapid expansion of consumer capitalism, in which mass marketing played a significant role in creating new buyers for products, helped to increase the magnitude of Christmas giving. It also increased the presence of Santa Claus.

Today, Santa Claus is everywhere and anywhere during the month of December. The iconic tales are told and retold over and over again, and nobody seems to mind the repetition. His presence is felt throughout the month – in fact, he ultimately helps define the spirit of the season and is the representation of consumer culture.… Strange to think that it all started with a Christian bishop who spent his life helping the poor and the sick.