Now that the exodus from Sochi, Russia is all but complete, our reflex is to put on a pair of rose-coloured glasses and talk about how great everything was, how inspiring the athletes were, how great we felt about our country’s performance. We’re not exactly missing the point of the Olympics, but there is so much more to the Games that deserves to be remembered. And, particularly with the Sochi Games, it’s not all rosy.

The athletes deserve every ounce of credit for giving sports fans all they could have asked for and then some. Their triumphs were inspiring, their failures were tragic, they made us proud even when they didn’t achieve what they’d hoped for. They did everything they could to make these Games a success.

But Games aren’t just the games; the athletes aren’t responsible for the venues, the planning, the politics or anything that doesn’t directly involve competition. And that’s where Sochi let us—and them—down.

The Olympics are meant to be apolitical, but it’s impossible for any group of humans to be so apolitical as to ignore the problems associated with holding the Olympics in a Russian resort town. Russia’s current government is institutionally discriminatory towards people who identify as LGBTQ; some of the athletes who competed in Sochi—almost certainly more than we realize—belong to that group, and so were directly subject to that institutional discrimination. If any of them had spoken about that part of their lives they could have been arrested and fined—surely the reason we didn’t hear more athletes speaking up was their fear of the consequences. For the IOC to put the athletes in that kind of situation is inexplicable and raises questions about just how apolitical the organization truly is—or should be.

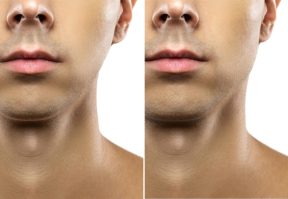

The IOC isn’t responsible for the facilities, though—Russia is—and that’s another area where the athletes were let down. Russia allegedly spent $51 billion—by far the most of any host nation and more than four times its initial budget—and somehow still ended up with unfinished buildings, insufficient infrastructure and subpar facilities. The media complained about unfinished hotels, toxic tap water, and a general lack of preparation; athletes bemoaned dangerous ski courses, a poorly built halfpipe, soft indoor ice, an inconsistent luge track, and generally poor quality in the venues.

But for all the complaints, at least most of the athletes faced equally disappointing conditions. What was more frustrating was that some didn’t seem to be competing on a level playing field. Figure skating has long been questionable in its judging and has a history of corruption, but there’s little doubt that off-ice factors had some influence on the results. French paper L’Equipe alleged a deal between US and Russian judges to ensure Canada wouldn’t top the podium in ice dancing or team figure skating—Canada won silver in both. But even more suspicious was Russian skater Adelina Sotnikova surprisingly beating defending Olympic champ Yuna Kim. One could argue either skater deserved the gold medal, but there’s the fact that one of the judges had already been suspended for fixing scores and another is married to the head of the Russian figure skating federation. The contest may have, in fact, been judged properly—but it sure doesn’t look that way.

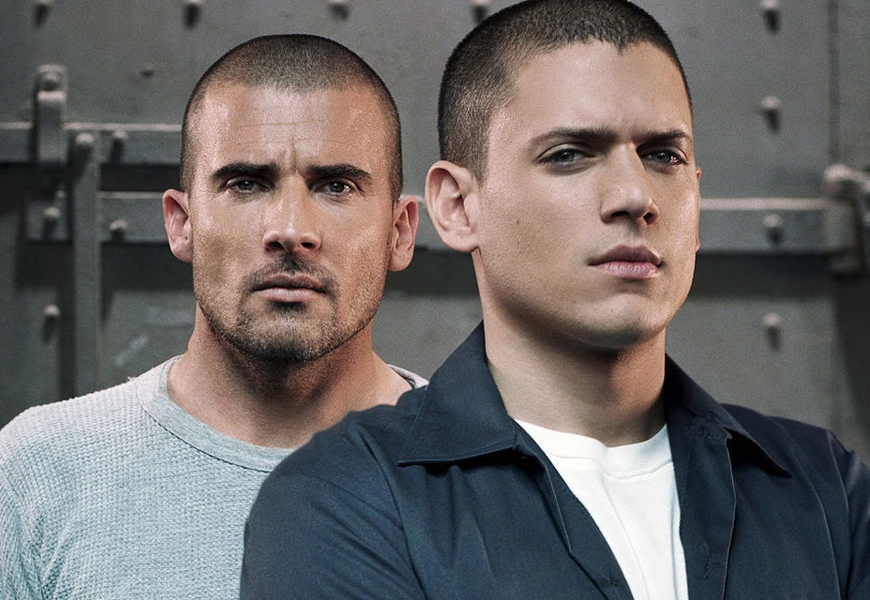

And then there were the ringers: non-Russian-born athletes won five of Russia’s gold medals and a bronze. Russia surely wanted to make a big impression while hosting the games—the same way Canada made its push to “Own the Podium” when hosting the Games in 2010—and so it pulled out all the stops to maximize its medal count. American-born alpine snowboarder Vic Wild won a pair of golds for Russia—but only because he qualified for citizenship after marrying a Russian woman, Alena Zavarzina, and was pushed out of the U.S. program by a lack of funding. Victor Ahn, on the other hand, won three golds and a bronze as a hired gun. After failing to qualify to represent his native South Korea in the 2010 Games, Russia enticed Ahn with a smooth citizenship path and the promise of financial compensation. Is it fair for athletes to compete for other countries when their homelands won’t help them out? Maybe, but it doesn’t seem fair for one country to use money and passports to cherry-pick top foreign athletes.

About the only thing Russia did without complication was make sure the Olympics started and finished on time and all the events happened, and really, that’s the lowest bar a host nation could face. The world’s best came to Sochi, competed in the events they had planned to, won medals—or didn’t—cracked jokes about bathroom facilities and stray wolves roaming the athletes’ village, and then went home to train for the next competition. Russia still holds more mystery than magic for those of us who watched from home, and for most of us, the Sochi Olympics will be remembered more what went wrong than what went right.